It was an innocuous summer day in 2009 when DeVonte Jones first exhibited signs of schizophrenia. Jones and his mother were attending a baseball game at Wavering Park in Quincy, Illinois, a sprawling facility of playground equipment, pavilions, grills, and, of course, baseball diamonds. Jones was just a teenager at the time.

It was an innocuous summer day in 2009 when DeVonte Jones first exhibited signs of schizophrenia. Jones and his mother were attending a baseball game at Wavering Park in Quincy, Illinois, a sprawling facility of playground equipment, pavilions, grills, and, of course, baseball diamonds. Jones was just a teenager at the time.

“He snapped out and just went around and started kicking people," says Jones' mother, Linda Colon. It wasn’t long before someone called the police. Jones was arrested and taken to the Adams County Jail, where he was charged with aggravated battery. Jones still asserts that he has no recollection of the event.

Jones was sentenced to probation and attended therapy to help cope with his schizophrenia. He was prescribed multiple medications, but none of it, Colon says, helped her son. When Jones was later caught using marijuana to help treat his symptoms, it began a merry-go-round of repeated incarcerations and releases, making Jones one of the many past juvenile offenders who become part of the recidivism statistics.

Nearly two million juveniles are arrested within the United States each and every year. Of those two million an estimated sixty-five to seventy percent of them are diagnosed with a mental health disorder. While severe psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are rare among incarcerated youth, one quarter suffer from some form of mental illness severe enough to hinder their ability to deal with the everyday pressures of adolescent life. Furthermore, a full two-thirds of the juveniles in detention affected by mental health issues have been diagnosed with more than one disorder. One of the most prevalent disorders within the juvenile systems is substance abuse. A random sampling of nine sites carried out by the Department of Justice showed that, of all male juveniles arrested and taken to these sites, half of them tested positive for at least one drug. Other commonly seen mental illnesses are anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorders.

A Lack of Mental Health Tools

Frequently, juveniles with mental illnesses that end up in the criminal system are there as a direct result of not having access to treatment for their illnesses within their community. This can be due to a lack of funds to pay for care, a lack of care centers in their immediate area, and also the social stigma still often attached to people with mental health disorders. In custody, juveniles’ access to care is just as poor. Mental illnesses are often difficult to treat in juveniles, due to the simple fact that they are still growing mentally and emotionally, and experience strong hormonal shifts. This can create frequent and distinct fluxes in their symptoms, and thus requires they receive ongoing assessment and treatment.

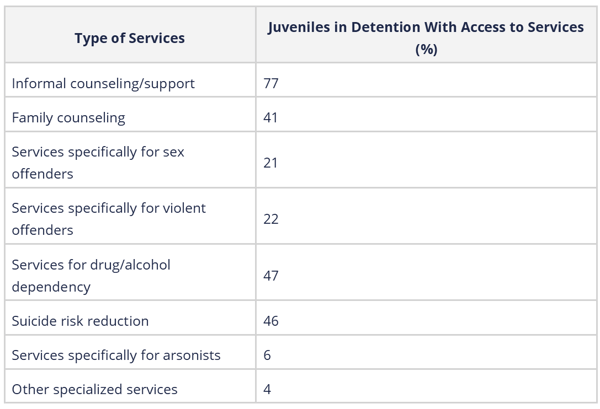

Within juvenile detention facilities, there is often a lack of any in-facility screening programs, let alone treatment options. A study1 published by the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law showed exactly the extent to which detention facilities are failing to provide mental care to the juveniles in their care:

Meeting the Standards

Currently, the National Commission on Correctional Health provides published standards of care for juveniles in detention facilities. Summed up, the standards require: detainees be screened quickly for mental disorders and current medications, and any medication regimens not be interrupted; treatment plans be developed by qualified mental health professionals, documented, reviewed regularly, and made known to staff that interact with the juvenile; medication should only be used as intended, not as a form of behavioral control; the facility must have suicide prevention measures; and, juveniles should be provided with information for mental health care outside of the facility prior to release.

Meeting these standards, unfortunately, is optional for facilities, and very few actually do so. One of the most prevalent reasons for this is because many facilities are running with very limited resources, and simply cannot meet the staffing requirements that would be necessary to enact all of the NCCHs standards. This furthers the issue that juvenile offenders have with actually receiving assessment and treatment for their mental illnesses. As a result, the repeat offender rate for juveniles with mental illnesses is a shocking seventy-five percent within three years after release.

Some states, however, are on the path to helping juvenile offenders with mental illnesses become rehabilitated, and thus be able to stay within their communities rather than end up as repeat offenders. Multisystemic Therapy (MST) is one of the programs successfully implemented across the country as an alternative to juvenile incarceration.

In a time when people with mental health issues end up in jail due to a lack of hospitals equipped to help them, programs like these serve as examples to the rest of the United States. The effect that proper mental health assessment and treatment can have on the lives of juvenile offenders with mental illnesses is undeniable. It is only with proper diagnosis and treatment that these children will be able to become happy, functioning members of society.

1 Mental Health Care in Juvenile Detention Facilities: A Review. Rani A. Desai, Joseph L. Goulet, Judith Robbins, John F. Chapman, Scott J. Migdole, Michael A. Hoge. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online Jun 2006, 34 (2) 204-214.